Hannaford light (#nz44)

Whilst this windmill was never constructed at full size, a model appears to have been produced and shown to all who showed an interest.

Background of T B Hannaford

T B Hannaford appears to have carried on various activities in Auckland, before he came up with his windmill lighthouse plan. From 1863 he ran a staffing agency: Auckland Star, Volume XIII, Issue 3702, 22 June 1882WANTED, at Hannaford's Auckland Registry (established 1863), good respectable Female Servants of all classes.He also did business as a land agent: Daily Southern Cross, Volume XXIII, Issue 3119, 16 July 1867

WANTED, at Hannaford's Auckland Hogistry, (established 1863), Barman for first-class city hotel; (none but professionals need apply).

WANTED, at Hannaford's Auckland Registry (established 1863), 2 Generals (small familys), Mount Albert.

WANTED, at Hannaford's Auckland Registry (established 1863), Hotel Man Cook (Thames) wages 30s.

WANTED, at Hannaford's Auckland Registry (established 1863), Female Servant (North Shore), no washing, wages 12s.

WANTED, at Hannaford's Auckland Registry (established 1863), Housemaid (gentleman's family. Mt. Eden).

A BARGAIN.- 63 Acres of really Good LAND at Mangapai, water frontage, 6s. per acre net.— T/B. Hannaford, Land Agent, High-street.These activities gave rise to some magistrates court appearances: Auckland Star, Volume I, Issue 173, 29 July 1870

Defended Cases. T. B. Hannaford v. G. Rodgers, claim of £5 16s 6d, for rent alleged to be due. An agreement between the parties was produced, and evidence received from plaintiff and defendant. Judgment for defendant.Auckland Star, Volume I, Issue 251, 28 October 1870

Samuel Partridge v. T. B. Hannaford : Claim, £1 14s. 8d. Judgment for plaintiff.Auckland Star, Volume II, Issue 449, 19 June 1871

POLICE COURT.—Monday.A complex case involving purjury, drukedness and more Auckland Star, Volume III, Issue 857, 3 December 1872 A frivolous case about a waistcoat Auckland Star, Volume IV, Issue 915, 12 February 1873

Before Thomas Beckham, Esq., R.M.

Drunkenness. - Thomas B. Hannaford, for being drunk and disorderly, was fined 20s and costs, or to be imprisoned 48 hours, with hard labour.

LARCENY, Ellen Parker was brought up on a Warrant, charged with stealing Mr Thomas B. Hannaford's white summer waistcoat, valued at 7s., on the 15th day of December, 1872. The accused, a decent looking poor woman, stated that the complainant gave her the waistcoat. Mr Broham stated that since Mr Hannaford had taken out a warrent for the apprehension of the accused he had got out of the way, and could not be found to substantiate the charge. The Chairman said it was a pity that something could not be done to prevent Mr Hannaford's vagaries in taking up the time of the Court about such frivolous matters. The charge was dismissed.He had varied business interests Auckland Star, Volume I, Issue 252, 29 October 1870

T. B. HANNAFORD, LAND, HOUSE, AND GENERAL COMMISSION AGENT, PUBLIC WRITER, ACCOUNTANT, AND COLLECTOR, SERVANTS' REGISTRY OFFICEand he also advertised "infallible remedies" Auckland Star, Volume XXII, Issue 4233, 3 January 1884

DEAFNESS ! — Those distinguished London Auriculists (Doctors Harvey and Pritchard) infallible remiedies. Desciptive pamphlets forwarded on receipt of stamps for postage — T. B. Hannaford, Auckland.The staffing agency also included a matrimonial agency. New Zealand Herald, Volume XIX, Issue 6414, 8 June 1882

MATRIMONIAL.— A young gentleman with a fair amount of capital is desirous of securing a life partner. The lady's dowry must include a spotless reputation and a good education; those conjoined to a comely form preferred. This is a genuine want. Full particulars and photo, at Hannaford's Agency.Letter to the paper about construction of a sea wall Auckland Star, Volume IV, Issue 934, 7 March 1873 and followup Auckland Star, Volume IV, Issue 1011, 16 April 1873 An amusing article about his lost pair of trousers Auckland Star, Volume IV, Issue 1024, 1 May 1873

Original windmill scheme - mechanically striking a bell

The first published reference I've seen to a windmill scheme was in 1884, when T B Hannaford in one of many letters about his plan described merely a windmill powering a hammer to strike a signal bell Auckland Star, Volume XXVI, Issue 4449, 18 August 1884PREVENTION OF WRECKS.A brief mention in Timaru Herald, Volume XL, Issue 3096, 26 August 1884 is merely a summary of the Auckland report:

Suggestions to Ensure the Safety of New Zealand Coasts,Mr T. B. Hannaford, of this city, has evolved a plan whereby he claims that, at trifling expense, the absolute security of our New Zealand coasts could be ensured. This scheme he has submitted in a letter to His Excellency the Governor, who replies as follows :—

"Govt. House, Wellington,

"23rd Juno, 1884,

"T. B. Hannaford, Esq.,

"Sir, — I am desired by His Excellency the Governor to acknowledge, with his thanks, the receipt of your letter of the 4th inst. containing a suggestion for the placing of turrets or dwarf towers on the small rocks and reefs near the coast of New Zealand. — I am, sir, your obedient servant,

F. W. Pennefather, Private SecretaryThe scheme thus submitted to high authority seems worthy of consideration, and will be found described in the following letter from Mr Hannaford : —

"Sir, - The frequent wreckage and accidents to steamers and sailing vessels on the New Zealand coasts, I have reasons for believing, are getting these islands an evil name. Many a small sunken rock and insignificant reef is dotted here and there from north to south on both East and West Coasts. But small and insignificant as they may be, they are all sufficient to wreck a noble steamer or a stalely ship! Now, were I to recommend the erection of lighthouses on all these points of danger, with the necessary complement of keepers, I should be jeered at for a fool, and entitle myself for a lodgment at the Whau. But, sir, something should be done to warn mariners of their dangerous proximity. And this is what (with your kind permission) I desire to lay before your scientific readers for their grave consideration. On the most dangerous of those small sunken rocks or reefs, let skeleton turrets or dwarf towers be erected (something similar to our firebell supports, only of iron instead of wood, and therein hang a loud-toned bell, the tolling of which could easily be accomplished by a windmill fixed on the top of the bell turret or tower. The bell, by the aid of a cog wheel, could be made rotary, so that the hammer, working in a fixed groove, would strike on every portion of the bell's circumference, instead of constantly infringing on one particular spot, which oftentimes is the cause of bells being cracked. The more furious the storm, the greater the volocity of the 'fans,' and louder and more rapid would be the clangour of the bell. I hold that such an arrangement would be a priceless blessing to seafaring men approaching or leaving our coasts, and the cost of each would be comparatively small. Many engineers in New Zealand would not only in a short space of time produce working drawings of what I have so feebly shadowed out, but improve upon it, such as the addition of 'windgauges,' which would not only register the wind's force, but the day and hour of such registrations at one particular point, so as to compare with other portions of the seaboard, at the same minute of time. All the attention of these ocean sentinels would require would be an occasional coat of paint, a little oil to the works, and it may be, replacing a broken fan ; added to which they would, in daylight, be admirable beacons to guide masters of vessels to their desired havens.— I am, &c., T. B. Hannaford."

Prevention of Wrecks. — Mr T. B. Hannaford, of Auckland, has submitted a letter to His Excellency the Governor, in which he suggests that there should be erected on reefs and rocks in dangerous positions on the New Zealand coast, skeleton turrets or dwarf towers, something similar to fire-bell supports, but of iron instead of wood, in which a loud-toned bell should be hung, to be tolled by a windmill fixed on top of the turret. The more furious the storm, he points out, the greater the clangor of the bell, and in fair weather the turrets would act as beacons. The cost of maintenance, he thinks, would not exceed that of an occasional coat of paint, and perhaps the replacement of a broken fan.Some encouragement on the suggestion appeared via letters to the paper: Auckland Star, Volume XXVI, Issue 4459, 29 August 1884

Sir, ln your issue of August 18th I notice with great pleasure a letter from the Governor's Private Secretary to Mr T. B. Hannaford, of this city, thanking that gentleman for a suggestion which is of very great importance to the travelling public. I myself have had long experience, and many hairbreadth escapes from the dangerous rocks upon our coasts, and with your kind permission, sir, desire to endorse all that has been so well stated by Mr Hannaford in your columns; and to thank that gentleman, in the name of a large family, who are in continual peril when travelling at night, from the numberless unguarded reefs upon our coastline. This is indeed a practical suggestion, which would be hailed by many in Auckland with great satisfaction. It is well remembered by me, now more than a quarter of a century since, what a pleasing sound was the bell buoy at Liverpool, and how useful it was in directing vessels in distress into the dangerous channel up the Mersey. Personally Mr Hannaford is a stranger to me, but it is nevertheless a pleasure to thank that gentleman for his letter in your issue of the 18th ult. — I am, etc., Richard Marsh.There was some interest in bringing the scheme to the attention of Parliament Auckland Star, Volume XXVI, Issue 4461, 1 September 1884

Mr T. B. Hannaford's scheme for the prevention of wrecks on the coasts of New Zealand is to be brought under the notice of the House of Representatives by means of a petition. The proposed apparatus has already been described in our columns, and the inventor has since brought the subject directly under the notice of many prominent citizens. The result is that a memorial is being extensively signed praying the House of Representatives to give favourable consideration to Mr Hannaford's petition in the interest of the public safety, and the credit of the colony. His Worship the Mayor's signature heads the list, and many other influential names are being appended.

Open discussion (or confrontation) on the matter took place via the Auckland newpapers letters columns Auckland Star, Volume XXVI, Issue 4464, 4 September 1884

Prevention of Wrecks.with replies soon forthcoming Auckland Star, Volume XXVI, Issue 4467, 8 September 1884

(To the Editor,)

Sir,—With reference to the above allow me to say how proximity to the "Spitbank" at Portsmouth is made known to mariners, There is a large flat-headed buoy moored bearing a cone-shaped framework some 12 or 14 feet high, within which is placed three hollow seats running from different points to the centre, each seat meeting a bell, mouth downwards. In each of these seats is a cannon ball, which runs down, on the buoy rocking, to the bell, giving out a very loud sound. No matter how smooth the water may be, this bell rings; in fact I have known the "Spit bellbuoy" to ring when Spithead has been as smooth the the paper I am writing on, and the swell of a passing steamer will ring it for hours. The contrivance was invented and patented by a Portsmouth man, and after some trials the Lords of the Admiralty adapted it, and I believe all shoals round the naval ports now have these buoys. I remember soon after the Spit bell-buoy came into use, a petition was presented by the residents of Southsea to the Admiralty to have it done away with on "account of the nuisance of its continual ringing," and yet the distance from its moorings to the nearest house is at least 2 1/2 miles. This very thing should be its strongest advocate. Before adopting any new-fangled "windmill" arrangement, it would be as well to inquire into the advantages of this to which I have referred.—Yours faithfully, EX-SOUTHSEAN, Brrighton Road, September 2, 1884.

Prevention of Wrecks.The paper soon declared a truce, declining to publish further letters on the matter Auckland Star, Volume XXVI, Issue 4471, 12 September 1884

(To the Editor.)Sir, —I notice in your issue of yesterday a letter from "Ex Southsean" in reference to the above, giving some particulars as to the Spit buoy at Portsmouth, and I certainly think with him that if the Government are thinking of a way whereby the frequent occurrence of wrecks around this dangerous coast may be avoided, this should be considered in preference to Mr Hannaford's (I believe) idea of the windmill arrangement. To my idea it is a cheaper as well as a more effective mode of warning our mariners of the proximity of rocks or shoals. The buoys cannot possibly get out of order, as the windmills might; and, as "Ex-Southsean" states, and I fully corroborate him, the slightest motion sets those "bell buoys" ringing, they are useful in fogs when there is scarcely any wind, or at any rate not enough to set going a windmill. I have heard the Spit buoy at Portsmouth ringing when fully 7 or 8 miles away from it and only a little wind stirring, and have set it ringing myself when in a small boat with just a touch of the hand, and at Southsea on the finest of days it can generally be heard, although perhaps slightly. As this has been proved by the naval authorities at Home to be thoroughly effective, it would be better to go in for a thing that has been so proved than to spend money on a thing that perhaps will not answer. Something most assuredly ought to be done to lessen the dangers of the coast of this country. — I am, etc.,

Portsmouth.

Collingwood-street, Sept. 4, 1884.Sir, — It is true that the poet wrote, "Fools rush in where angels fear to tread." Still, it is hard after a year's intense study, resulting in the evolution of what I dare to say is a grand scheme for the prevention of wrecks, to receive through the press a slap in the face from a brainless "Jack Pudding." There are some scribblers who can shed ink on no subject without writing themselves down asses at one and the same time. Your correspondent, "Ex-Southsean," in Thursday night's Star, is one of the number. Now, I would ask any sane man of what earthly use a cone-shaped framework 12 or 14 feet high (!) enclosing a peal of bells and a lot of cannon-balls, would be to mariners to warn them of the dangerous proximity of a sunken rock or reef 50 or more miles away from land? How much of that cone-shaped framework could be descried from the deck of a vessel in a gale of wind? I waive all intention of the important works my "new-fangled windmill arrangement" could carry out besides ringing ceaseless warning peals, and content myself with just these few words :— An object at rest (or if bobbing about would at a distance appear at rest) would not nearly be as likely to catch the eye of a sailor as another in pronounced motion, which would be the case with my "new-fangled windmill arrangement," through the revolvings of its "fans." —I am, &c.,

T. B. Hannaford.

Notices to Correspondents.

T. B. Hannaford. — We concur it is about time the controversy about "Prevention of Wrecks" was brought to a close. Thanks for your letter, which is declined, in pursuance of the opinion expressed in its opening sentence. The letters of "Ex-Southsean" and "Another Ex Southsean" on the same subject are also declined with thanks, as the correspondence seems likely to degenerate into personalities. All, we hope, will rejoice if the outcome of the present agitation is to secure greater security for "those that go down to the sea in ships", no matter whether it is by a cannon-ball or "windmill arrangement."

Some attention was indeed paid in Parliament Auckland Star, Volume XXVI, Issue 4475, 17 September 1884

Prevention of Wrecks. In the House yesterday afternoon, Sir George Grey presented a petition from Mr T. B. Hannaford, Auckland, praying the Government to introduce his system of belltowers as warnings on the coast.

Hannaforth continued to iterate on his proposal, such as adding luminous paint, and to write letters to the papers about it. Otago Daily Times, Issue 7068, 10 October 1884

PREVENTION OF WRECKS. TO THE EDITOR.

Sir,—The frequent wreckage and accidents to steamers and sailing vessels on the New Zealand coasts, I have reasons for believing, are getting these Islands an evil name. Many a small sunken rock and insignificant reef is dotted here and there from north to south on both East and West Coasts. But small and insignificant as they may be, they are all sufficient to wreck a noble steamer or a stately ship. Now, were I to recommend the erection of lighthouses on all these points of danger, with the necessary complement of keepers, I should be jeered at for a fool, and entitle myself to a lodgmont at the Whau. But, Sir, something should be done to warn mariners of their dangerous proximity. And this is what (with your kind permission) I desire to lay before your scientific readers for their grave consideration. On the most dangerous of those small sunken rocks or reefs, let skeleton turrets or dwarf towers be erected (something similar to our firebell supports, only of iron instead of wood), and therein hang a loud-toned bell, the tolling of which could easily be accomplished by a windmill fixed on the top of the bell-turret or tower. The bell, by the aid of a cog-wheel, could be made rotary, so that the hammer, working in a fixed groove, would strike on every portion of the bell's circumference, instead of constantly impinging on one particular spot, which oftentimes is the cause of bells being cracked. The more furious the storm, the greater the velocity of the "fans," and louder and more rapid would be the clangour of the bell, I hold that such an arrangement would be a priceless blessing to seafaring men approaching or leaving our coast, and the cost of each would be comparatively small. Many engineers in Now Zealand would not only in a short space of time produce working drawings of what I have so feebly shadowed out, but improve upon it—such as the addition of "windgauges," which would not only register the wind's force, but the day and hour of such registrations at one particular point, so as to compare with other portions of the seaboard, at the same minute of time. All the attention of these ocean sentinels would require would be an occasional coat of luminous paint, a little oil to the works, and it may be, replacing a broken fan ; added to which they would in daylight, and through the luminosity of the paint at night likewise, be admirable beacons to guide masters of vessels to their desired havens.—l am, &c, T. B. Hannaford. Auckland, October 2.

The parlimentary committee declined the suggestion. New Zealand Herald, Volume XXI, Issue 7149, 15 October 1884

PARLIAMENTARY NEWS.

MR. HANNAFORD'S PETITION. The Public Petitions Committee reports as follows on the petition of Mr. T. B. Hannaford, of Auckland : —"The committee having referred the petition to the Marine Department, have been informed by that department that the petitioner is in error with reapecfc to his statement that the New Zealand coast is especially dangerous from sunken rocks and reefs. They are also informed it is not desirable to carry out the suggestion of the petitioner that windmill bell turrets should be erected on sunken rocks and reefs. The committee cannot, therefore, recommend the prayer of the petitioner."

Not disheartened by the rejection, Hannaford tried for a less ambitions first installation. Auckland Star, Volume XXVI, Issue 4521, 25 November 1884

Mr T. B. Hannaford having failed to induce the House of Representatives to adopt his skeleton Windmill Iron Bell Turret for use throughout the colony, is now endeavouring to persuade the Harbour Board to erect one at Rangitoto Reef, in the place of the proposed stone beacon.New Zealand Herald, Volume XXI, Issue 7185, 26 November 1884

HARBOUR BOARD.Hannaford got drawings and a model made New Zealand Herald, Volume XXII, Issue 7248, 10 February 1885Beacon at Rangitoto.—Mr. T. B. Hannaford submitted that his skeleton windmill iron turret might be erected on this point instead of the stone turret. It would, he said, cost less, and be far more likely to catch the eye of mariners. Referred to the Engineer to report on.

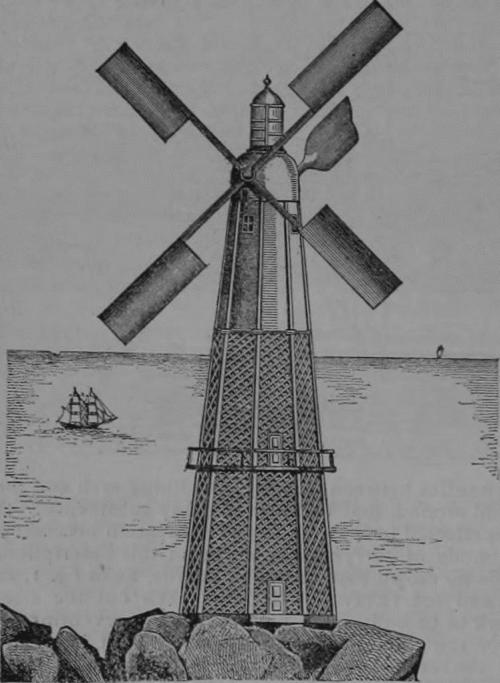

Mr. T. B. Hannaford has, we understand, just executed drawings of the iron windmill bell tower, which he proposes to place on reefs off the coast. These will be forwarded to Mr. George Fraser. The drawings show the reef piers as well as the other rings up to the tower's crown—showing the ribs in three tiers. The tower is three tiers in height, that is to say, of 20 feet each, or 60 feet in all. He has likewise made a model showing how, through the revolvings of the windmill, it tolls the warning bell. The two main features of Mr. Hannaford's invention are — first, sound to draw attention to the tower's direction or location, and second, sight arrested by the revolving fans showing the reel's proximity.

Updated windmill scheme - incorporating a dynamo

By 1885, the windmill scheme had been enhanced to incorporate electrical generation, to power the lighthouse light: Auckland Star, Volume XXVI, Issue 98, 4 May 1885As well as Auckland, Hannaford set his sights on other coastal towns. Taranaki Herald, Volume XXXIII, Issue 6778, 10 June 1885NEW SKELETON LIGHT HOUSE.

Since attention was drawn in our columns to Mr T. B. Hannaford's invention of a "skeleton circular bell-tower lighthouse" the subject has been looked into by a local engineer of first-class ability, and he has reported most favourably of the idea. The structure, it is proposed, shall stand on eight dwarf piers, built on the rocks or reefs, against which the mariner is to be warned. The tower is to be of iron, and in three tiers — each tier 20 feet in height, or from base to crown 60 feet. The top tier is the machine-room and would be floored with iron. The machine-room would be reached by a spiral iron and railed stairway on the inside of the tower, ending in a man-hole. As each tier is composed of eight ribs, and as the whole structure is put together with nuts and bolts, it will be seen that should it be necessary (say in war time) to take it down, the work could be carried out at three different points of its altitude at one and the same time, and eight dwarf piers being constructed on another reef or rock, the entire tower, less the machinery, could be reerected in a day. The chance that a hostile cruiser would have of eecape from wreck, if it steered by the tower after it was moved from its former position, would be slight. The special feature of the invention, howover, is the windmill arrangement at top, which is to serve the triple purpose of attracting the attention of mariners in daytime, ringing the lighthouse bell in fogs, aud generating electricity for the light. Looking at the whole thing as now evolved from the brain of the inventor, it seems a matter of surprise that such an idea was not long ago adopted for the protection of shipping. The "skeleton" idea is a good one, for the tower offers little resistance to the winds or waves, and its stability would be undoubted. Lighthouses erected on this principle would be most serviceable for use at the approaches to harbours, and as Mr Hannaford at present despairs of persuading the General Government to give his invention a trial, it might be worth while for our Harbour Board to come to terms with him, or use their influence with Government on behalf of a really useful and ingenious contrivance.

HARBOUR BOARD.He also continued to resubmit to the Auckland Harbour Board. New Zealand Herald, Volume XXIII, Issue 7581, 10 March 1886Lighthouse. — A letter from Mr. T. B. Hannaford, of Auckland, re a Skeleton windmill bell tower, was received.

HARBOUR BOARD.Via a report on his spending time in gaol, we learn that the Tasmanian Government had also been corresponded with. New Zealand Herald, Volume XXIII, Issue 7658, 8 June 1886Mr. T. B. Hannaford again wrote respecting his iron skeleton windmill bell-tower, and asked the Board to reconsider their decision, and renewed the offer previously made. The Chairman said there was no use in sending it to a committee unless there was some new feature. Mr. Aickin said there was a new feature; they had a new Engineer since they had Mr. Hannaford's last rigmarole, and he moved that it be referred to the Engineer on Mr. Hannaford furnishing details. The motion was agreed to.

Yesterday Mr. T. B. Hannaford, having "taken out" his fine and costs, in the case of Garrard v. Hannaford, in Mount Eden Gaol, was restored to the bosom of his family. As he says, very truly, he does not feel in the best of trim to take up the tangled skein of his matrimonial agency business again, or to enter into a correspondence with the Tasmanian Government over the merits of his windmill bell-turret system, after a fortnight's stonebreaking in the Mount Eden quarries. It appears that during his incarceration a letter has come to hand from the Tasmanian Goverment notifying him that his invention has been referred to the Lighthouse Committee, and, if after examination of its merits, the report is favourable, he will be further communicated with. Mr. Hannaford intends to prepare a precis of his case for transmission, in the first place to the Minister of Justice, and then to the Assembly, as he is under the belief that a gross miscarriage of justice has arisen.Questions were again raised in parliament. Auckland Star, Volume XVII, Issue 157, 7 July 1886

PARLIAMENTARY NOTES.When asked, the answer was a rejection: New Zealand Herald, Volume XXIII, Issue 7698, 24 July 1886Mr Hannaford's Bell Tower.

Mr Buckland intends to ask the Minister of Marine on Friday next if his attention has been drawn to Mr Hannaford's newly invented "iron skeleton windmill bell tower lighthouse," and if he will grant Mr Hannaford clerical assistance towards making working plans for the same.

A further rejection from the Auckland Harbour Board. Auckland Star, Volume XVII, Issue 103, 14 July 1886THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY.

Mr. W. F. Buckland asked the Minister of Marine if his attention has been drawn to Mr. Hannaford's newly-invented New Iron Skeleton Windmill Belltower Lighthouse," and if he will grant Mr. Hannaford clerical assistance towards making working plans for the same.

Mr. Larnach said this matter had been reported upon by the Public Petitions Committee last session as being useless, and the Government did not intend to give any clerical assistance.

HARBOUR BOARD.An enquiry with the government was seemingly having a little more success. Auckland Star, Volume XVII, Issue 178, 31 July 1886THE Windmill Bell Lighthouse. Mr T. B. Hannaford wrote asking the Board to refrain from deciding on erecting a beacon on Rangitoto reef until the fate of his "Iron Skeleton Windmill Bell Lighthouse" now before the House of Representives is known. He had reason to believe the scheme would meet with favourable consideration at thn bands of the New Zealand Marine Department. It was decided to inform Mr Hannaford that the Board do not consider it desirable to erect a windmill bell tower on Rangitoto Reef.

As well as pressuring officials, the "invention" was shown at a public meeting. From the Evening Post, 16 August 1888:PARLIAMENTARY NOTES.

Mr Hannaford's Petition

Mr Hannaford's petition relative to the windmill bell turret lighthouse has been referred by the Petitions Committee to the Government for consideration.

Auckland: A public gathering last night at the Oddfellows' Hall, the Mayor presiding, inspected a model of Hannaford windmill bell tower iron lighthouse, and after hearing explanations of the invention, resolved respectfully to ask Government to give it a trial at their earliest convenience.Rather longer pieces about the same meeting appeared in the New Zealand Herald, Volume XXV, Issue 9134, of the same date (16 August 1888):

and the Auckland Star, Volume XIX, Issue 192, 16 August 1888THE HANNAFORD BEACON AND LIGHTHOUSE.

A meeting convened by His Worship the Mayor was held in the Cook-street Hall last night for the purpose of hearing an explanation, and inspecting a model and drawings of the lighthouse invented by Mr. T. B. Hannaford. There was only a moderate attendance. His Worship the Mayor presided, and read letters of apology for unavoidable absence from Messrs. Merritt, Tebbs, Lodder, Boylan, Bates, and Mr. Worthington, and Mr. Herapath apologised for Mr. Errington's absence.

The Mayor said that Mr. Hannaford was the inventor of a patent lighthouse, based on a new principle, and claimed for it that it was inexpensive, practical, and can be used on any part of their coasts, or any other coasts, and that it was superior to any lighthouse ever invented. It had been inspected by visitors and by local engineers, who had expressed individual opinions, and he (the Mayor) thought that if this lighthouse was of the great public benefit claimed for it by the inventor it was only right that he should call a public meeting in order that those capable of giving an opinion might give a combined opinion, and if this was favourable it would give to the invention a status which Mr. Hannaford could not individually do. He had expected that there would have been a large attendance of experts whose opinions would settle on the utility or otherwise of the invention of which the model and working plans were now before them. He would call on Mr. Hannaford to explain his invention.

Mr. Hannaford said that for many years he had had the idea that he could invent a lighthouse unlike any other in the world. He was no copyist, for he firmly believed that there was not in the world anything at all like the Hannaford lighthouse. It had a fault. It did not provide billets. As he was rather deaf, and probably gentlemen present would like to ask some questions, he had asked Mr. S. M. Herepath to explain the model and drawing.

Mr. Herepath then thoroughly explained the model, from the concrete foundation, upward through the iron structure to the dome and lights. He pointed out that the object of the windmill was to turn a dynamo which would store electricity, and revolve the fans and ring the alarm bell when the wind failed. All these features were elucidated by the working model, and plans prepared by Mr. Herepath himself.

Mr. Purbrook, electrician, explained how the electricity was stored, capable of furnishing 15,000 candle-power for fourteen days' supply. He answered several questions in further explaining the manner in which the reserve was made. In reply to the Mayor, he said he did not propose to utilise the tidal force, as the result for the cost would be too small. In answer to Mr. Pond, Mr. Purbrook said that 6 h.p. would be sufficient.

Mr. Pond said that if that was assumed there would be a hiatus at some time, and duplicates would be necessary.

Mr, Purbrook acknowledged that duplicates would be necessary in case of accident, and in places where calms existed it might be necessary to have an engine.

Mr. Pond asked if Mr. Purbrook would be justified in recommending that a six horse-power nominal would be sufficient to supply 15,000 candle power light and storage.

Mr. Purbrook said that the power obtained from the windmill would be in excess of six horse-power; six horse-power would be required in direct action for the light.

In reply to other gentlemen, Mr. Purbrook explained briefly the storage cells and how they were utilised. They took a little more than double the time to charge that they did to discharge, but the storage took place day and night, and the lighting only went on at night, and that was where he gained. The light power would be generally from the storage cells, which would be supplied by the dynamo, but direct action could be used when the wind was favourable.

Mr. Hannaford made some further explanations. Sir Saul Samuel had recommended him to go to New South Wales, but he had not been thirty years in Auckland without having a love for it, and if he erected one of those beacons in New Zealand he would have orders for a dozen or a score of them. As the Mayor was aware, Lord Brassey, who would no doubt be the First Lord of the Admiralty, had a high opinion of the invention. He (Mr. Hannaford) was convinced that if allowed to put up one of these beacons it would be the best thing that could happen in New Zealand. The cost would be about £3000 he estimated, and if he was one of the magnates of the city there would be no difficulty in the matter.

Mr. Atkin said he would like to see the electric scheme applied to the windmill on the hill.

Mr. Purbrook said it would cost as much to attach it to that as to the lighthouse. It was a mere question of expense.

Mr. S. M. Herepath moved, "That this meeting having heard the inventor's explanation of the principle and details of his invention, respectfully ask the Government to give it a trial at their earliest convenience."

The motion was carried unanimously.

Mr. Hannaford returned thanks, and a vote of thanks to the chairman terminated the meeting.

Various other newspaper reports appeared about the invention, including a long piece in the Auckland paper Observer, Volume X, Issue 590, 19 April 1890:THE HANNAFORD BEACON.

PUBLIC MEETING

A public meeting, summoned by His Worship the Mayor (Mr A. E. Devore), was held in the Oddfellows' Hall, Cook-street, last evening, for the purpose of hearing an explanation of Mr Hannaford's electric beacon. There was a large attendance, His Worship the Mayor being in the chair.

The Chairman read letters of apology for unavoidable absence of Messrs Merritt, Tebbs, Lodder, Boylan, Bates and Worthington, and Mr Herepath apologised for Mr Errington's absence.

The Chairman stated for what the meeting had been called. He thought it was a very important subject, and he was of opinion that they should have an opinion of experts on the subject.

Mr Hannaford said that as he was rather deaf he had asked Mr Herepath to explain the working of the lighthouse. He firmly believed that there was nothing in the world like the Hannaford lighthouse. It did not provide billets, which might be reckoned a great fault against it.

Mr Herepath explained the construction and working of the lighthouse, of which a full description has already appeared in our columns, and illustrated his remarks by means of the working model.

Mr Hannaford said, in reference to the registering of the force of the wind current by means of the mechanical working of the lighthouse and the registering by the Scientific instruments in the lighthouse shaft, a very valuable knowledge of the wind currents would be obtained.

Mr Purbrook, electrician, explained the working of the storage cells and the lighting of the lighthouse. He answered several questions bearing on the matter. In reply to Mr Pond he stated that his 15,000 candle power light would be obtained by six-horse power through his storage cells. Mr Pond said that experience had shown that 50 per cent, was all that was really available in cases of that sort owing to waste, leakage, etc,, therefore twelve-horse power would be needed. He explained how duplicate lights, storage cells, and dynamo would be required in dase of accident. Mr Purbrook acknowledged that such duplicates would be necessary in case of accidents, and also a steam engine in case of calms. Mr Pond asked if Mr Purbrook would feel justified in recommending a six-horse power nominal as sufficient to supply 15,000 candle-power light and storage. Mr Purbrook, in reply, stated that the power to be obtained for the windmill would be in excess of six horse power, which was all that was necessary for the light. He afterwards explained that as the light'would only be necessary for a third of the time, the windmill action would be storing two-thirds longer than the electricity was being used up. In reply to other questions, he explained that the waste from the storage cells would hardly amount to anything in six weeks, and the keeper could always regulate the supply so as to keep them up to the right standard. Mr Hannaford made some further explanations, and showed the cost would not be much more than £3,000. Mr Atkin said he would like to see the electric scheme applied to the mill on the hill. Mr Purbrook explained that it would cost just as much as to apply it to a lighthouse. It was a mere question of expense. Mr S. M. Herepath then moved - "That this meeting having heard the inventor's explanation of the principle and details of his invention, respectfully ask the Government to give it a trial at their earliest convenience." The resolution was carried unanimously.

Mr Hannaford said a few words in reply, thanking the meeting, and a vote of thanks to the Chairman terminated the proceedings.

The Hannaford Light invention embraces a number of improvements in the construction of cast-iron towers for beacons or lighthouses, including windmill attachment for generating electricity, to be stored and used in the form of light for the lantern and of power to turn the windmill in times of calm and ring a bell during fogs. It is unnecessary now to describe the minutiae of the invention. Suffice it is to say that Mr Hannaford has worked at it for many years, making it as nearly perfect as possible, and that not only are the foundations and framework of the structure designed with great skill, but the electric and other attachments are devised so as to be almost entirely automatic in their action. Furthermore, engineers and electricians have examined the plant and models, and have been unanimous in their praise and commendation.

The inventor committed only one blunder, but that has proved a serious one. He did not take steps to protect his invention by letters patent. Want of the necessary means to do this may have been the reason of this omission; if so, it is but another exemplification of the truth (as old as Solomon) that the wisdom of the poor man is not regarded. Mr Hannaford put his trust in Princes — a very wise proceeding if he had secured letters patent, for nothing can be done nowadays without the powerful influence of those in position. Whenever a Cabinet Minister, or Government official, or distinguished visitor of any kind happened to be in Auckland, he was invited to see the model and plans of the Hannaford light; that windmill beacon was one of the recognised "lions" of Auckland; and the inventor was ever ready to explain the principle and details fully and clearly. Long residence in this wicked world ought to have taught Mr Hannaford that, if there was anything good and original in his ideas, they would soon become common property, under the circumstances. But, with a childlike trust, he kept on 'giving away' his invention. It would be easy to offer theories to account for this strange action. Perhaps Mr Hannaford thought Government officials and Cabinet Ministers were angels of light, incapable of stealing a poor man's ideas; perhaps he was unselfishly desirous of giving the world freely the fruits of his mental toils; or perhaps he was only the victim of one of those unfortunate lapses into blank idiocy to which all great men are said to be subject.

An article about this, apparently fairly serious suggestion, appeared in The Railroad and Engineering Journal in Feb 1891:

An Electrical Lighthouse. - The accompaning illustration, which is from the report of United States Consul Connolly, of Auckland, New Zealand, to the State Department, shows a lighthouse devised by Mr. Hannaford. a New Zealand inventor. It is an Iron tower, with a windmill attached, which furnishes power to run the electric light, storage batteries being provided to equalize the power and secure a regular, uniform light at all times. The inventor describes its working as follows :The illustration from the Railroad and Engineering Journal also apparently appeared in the Challenge Wind Mill and Feed Mill Company Trade catalog circa 1895, but I doubt that they were actually selling the device. [info]"The Hannaford light is in three tiers up to the revolving cupola (which carries the lamp), but, although the lamp, of course, revolves with the cupola, the arc within does not, but is always broadside to one desired direction, the lens pulley at its back facing (that is, the back of the lens) the land. Now, the lens has spring slides, which, when operated, send electric flashes that can be plainly discerned a distance of at least 30 miles inland. Each set of flashes are different from each other and represent the letters of the alphabet. An expert within the lighthouse can communicate to an expert many miles inland anything of importance - a supreme value in the event of a marine disaster or in war time. Again, the arc can be bent downward and upward, swayed to right or left, or all round the compass, thus making it a great ocean searcher. Again, the arc is automatic, does its own lighting and extinguishment to an hour, a minute, or a second. The storage of electricity is so novel that it is absolutely impossible to run short, even for an hour, of the full strength of the 15,000 candle-power, not even if there were a dead calm of six months' duration. Now, the illustration of the external appearance of Hannaford's light which I inclose would be misleading without explanation. There is, in reality, no lattice ironwork in the base and central tiers; on the contrary, they would be like the top tier. It was necessary to introduce this latticework in the working model so as to be able to observe the internal arrangements of the tower."

The advantages claimed are cheapness, durability, simplicity of construction and the ease with which the lighthouse can be erected or, if necessary, taken down and removed.